Since legislation demanded that the ominous words "contains sulphites" appear on the back of virtually every bottle of wine, the word "sulphites" has caused mass hysteria and hypochondria in wine consumers all over the world. Sulphur has since been miscast as a venomous villain: alleged giver of the infamous red wine headache, migraines, sinusitis, and more severe reactions.

Sulphur gets a bad rap. Blamed for itchy noses, flushed faces and of course, those notorious headaches, the public has singled out sulphur as the bad guy of the booze world. But (and there are numerous spoiler alerts ahead), sulphur is not the villain of viniculture. Quite the contrary in fact. Sulphur dioxide has more in common with Robin Hood than the Sheriff of Nottingham; more Severus Snape than Lord Voldemort.

As I stand in wine shops, pouring wine for the customers to taste and hopefully buy, there is always at least one customer who dramatically claims to be allergic to sulphur. In the nicest and least condescending manner, I try to explain to them that it is actually impossible to be allergic to sulphur, and the symptoms they’re describing don’t actually point to sulphur being the culprit. Of course, I am no doctor, but I am a professional wine drinker.

But before we get into that, let’s back up a little and first look at why wine needs added sulphur.

Sulphur dioxide is used in winemaking to protect the wine from unwelcome yeasts and bacteria, keeping the wine stable – particularly important for when the bottles have to be transported. Sulphur also protects the wine from oxidation – that is, it stops the juice from turning brown, and preserves the bright, fresh fruit flavours. It is used at most stages of white wine making from crushing to bottling. In red wine, it is used less so since reds naturally contain more antioxidants and antiseptics. But the finished product will always contain a certain level of sulphites. Yes, that’s right: sulphur is a by-product of alcoholic fermentation and is present even in ‘natural’ wines that contain “no added sulphur”.

An ancient pedigree

The process of using sulphites in wine has been around since as far back as ancient Rome. Back in Roman times, winemakers would burn candles made of sulphur in empty wine containers (amphora) to keep the wines from literally turning to vinegar. Sulphur started to be used in winemaking (instead of cleaning wine barrels) in the early 1900s to stop bacteria and other yeasts from growing.

Sulphur dioxide is certainly the most vital additive used in wine. Often, with a more minimalistic and natural approach to winemaking, it is in fact the only additive. Its value derives from its ability to execute several essential functions, akin to an all-purpose household cleaning product.

Tremayne Smith, winemaker at Fable Mountain Vineyards and his own label Blacksmith Wines, prides himself on making wines as clean as possible. “I’m not scared to use sulphur in my wines,” he says. “But there are some wines that I choose to use less sulphur in if it’s possible. I don’t have a set recipe for it. If the wine has a healthy pH and total acidity and we can use less sulphur then we do. But if the wine needs it, then we will add. Sulphur dioxide can mute the wine, but again it’s down to the cultivar and the style and when the SO2 was added. If you make a wine to be cellared for years in the bottle then SO2 is your friend.”

Am I allergic to sulphur?

Consumption of sulphites is generally harmless, unless you suffer from severe asthma or do not have the particular enzymes necessary to break down sulphites in your body, which is very rare. It is, in fact, estimated that about 1% of the population is intolerant to sulphur, and they will generally suffer from chronic asthma. Sulphites literally cannot provoke an immune response, which is required for something to be considered an allergy, and moreover, the levels present in most wines are not even worth discussing from a health perspective.

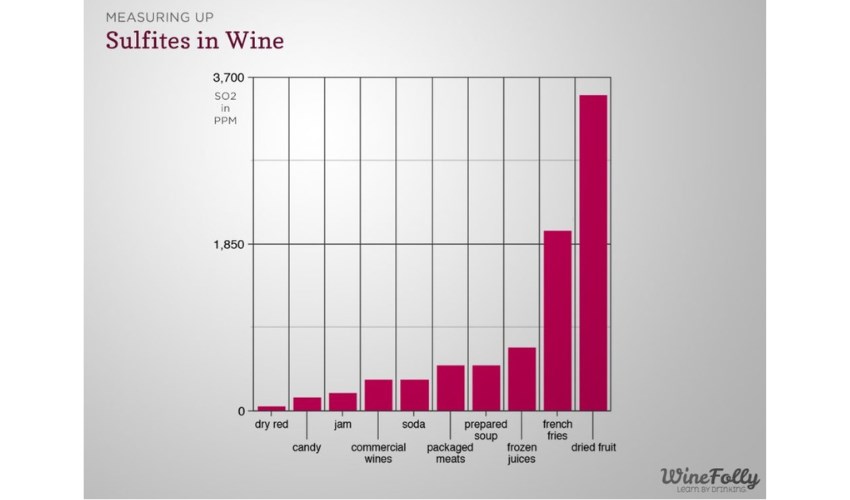

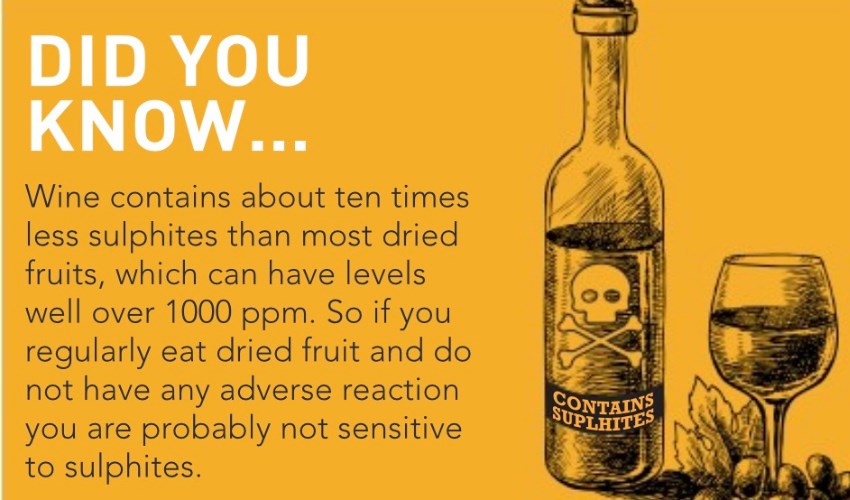

If truth be told, sulphur dioxide is used everywhere in the food industry, as it is a proven way to protect perishable items from oxidation. Chances are you will ingest more sulphites in your average restaurant dinner than from the glass or three of wine you sip with it.

So, do sulphites cause headaches? Many wine drinkers I’ve met inherently claim they do. Science says they don’t.

Sulphur is much more prevalent in common foods that are not singled out for triggering headache attacks, such as dried fruit. Organic wines contain lower levels of sulphites or have none added at all, but still people insist that any sulphur present is to blame for that post-wine headache. In addition, published medical research has not yet established any links between the presence of sulphites and headaches.

But people often complain of the dreaded RWH (red wine headache), and naively blame the sulphite. Ironically white and rosé wine is higher in sulphites than red wine, because generally they are not left on their skins after crushing. The tannins from the grape seeds and skins help prevent oxidation in red wine. For this reason white wines are more prone to oxidation and tend to be given larger doses of sulphur dioxide. They are however less likely to cause the consumer a headache, which suggests that it’s probably something else in red wine that’s responsible for the notorious red wine headache.

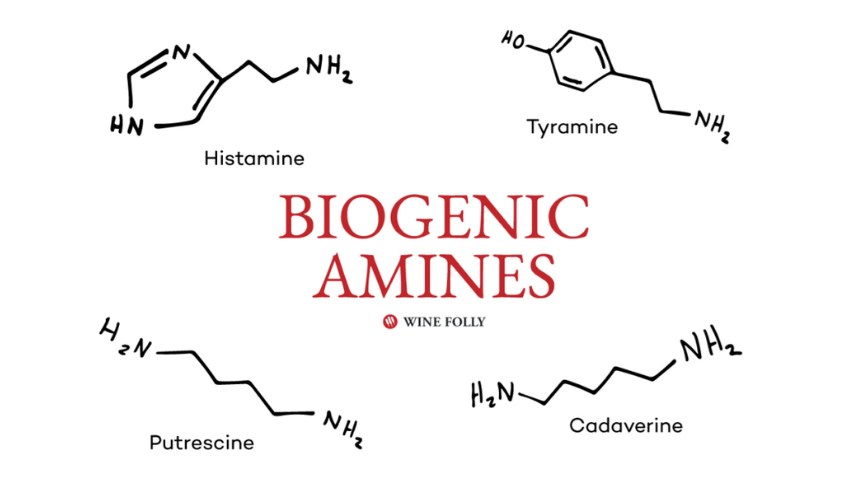

Meet the actual wine villains: Biogenic amines

Biogenic amines are organic nitrogen compounds that are produced naturally during winemaking. They include compounds like histamine, tyramine, putrescine, and cadaverine. Unlike sulphites, these substances can generate immune responses, exhibiting symptoms such as headaches or a stuffy nose and sometimes more serious effects.

A winemaking process called malolactic fermentation is a common source of amines. Virtually all red wines go through malo, as do buttery Chardonnays, as well as other bigger whites and sparkling wines. Aromatic and fresher whites, such as Sauvignon Blanc, are unlikely to have undertaken this process.

It’s also important to note that just because a wine is “natural” that doesn’t mean it has lower biogenic amines. In fact, native fermentations can sometimes increase the chance of compounds like histamine and tyramine forming.

So what can you do to minimise the perils of wine consumption and the so- called “sulphur headache”?

- Drink less!!

- Drink plenty of water.

- If the RWH is a common feature of your “wine flu” then taking an antihistamine before drinking red wine may assist you, but please consult your doctor first.

- Drink two cups of coffee prior to drinking red wine, as this is said to constrict blood vessels and limit migraines.

- Opt for lighter-coloured wines. This can reduce the effects, since the lighter hue means there are fewer tannins.

One of my favourite winemakers, Taras Ochota (RIP), once said “grapes have something to say”. If sulphur is used marginally it can cherish the voice of the grape; used in excess it will mute it. A century ago some wines would contain as much as 500mg of sulphur dioxide per litre; in South Africa today maximum levels of sulphur dioxide permitted in wines are 150 mg/litre.

Ironically, just as interest in the sulphite content of wine has increased, technology available to winemakers, as well as the on trend minimalist approach, means levels of sulphur in wine are actually at an all-time low. But of course these days everyone has a mouthpiece and the social justice warriors are always seeking something to shout about, whether it’s American politics, mask-wearing protocols or the terrible headache that they get the day after drinking too much wine.

So there we have it folks, sulphur is not a villain at all, it is actually just a defender of wine; a guardian angel protecting the integrity of the vintage. Sulphur dioxide is very safe, effective and useful in a well-made wine. As the Robin Hood quote goes “At the end of the day, I fight for those who cannot fight for themselves. If that makes me an outlaw, so be it. I’ve been called worse”. And that is the role of sulphur, helping the grape and winemaker achieve greatness in wine which would be unobtainable without SO2’s helping hand.

This article was first published in the Summer edition of On Tap Magazine.