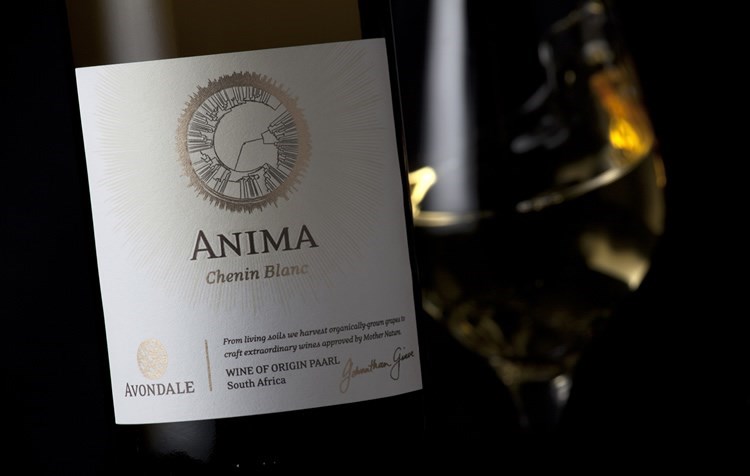

Bio-dynamic viticulturist Johnathan Grieve led the tasting of Chenin Blanc grown on the certified organic Avondale Farm on the outskirts of Paarl.

Wine critics tasted the wine in the cellar standing right next to an elegant cluster of Italian terracotta and local amphora (made by a potter using clay from the farm), underpinning the commitment to their motto, “terra is vita” (soil is life). The vessels may look seriously ancient - but the top seal heads are space-age.

Johnathan comments, “Amphorae were the original vessels used by the Romans and Greeks – long before steel, concrete or wooden barrels. We get great clarity, purity of fruit, lean tannins and natural acidity from slow fermentation on skins in amphora - especially with Chenin and with Rhône varieties such as Syrah, Grenache and Mourvèdre. The amphorae are porous and allow for micro-oxygenisation.”

Whole bunch fermentations in amphora and older, larger barrels using only natural yeast are the building blocks of Anima, Avondale’s flagship white wine made from Chenin Blanc. Johnathan emphasises that warmer, slower fermentations preserve the core fruit and create ageability in their wines, enabling them to hold back vintages until they are ready for release. (Anima 2015 was only released recently).

Bio-dynamic viticulturist and proprietor of Avondale, Johnathan Grieve.

Johnathan declares, “We use amphora to magnify the grape”. We tasted blending components of the 2015 Chenin vintage sourced from forty-year-old vines, matured in terracotta Italian and local amphora – as well as a component barrel-fermented for twelve months. The three building blocks of Anima were astoundingly different - ranging from the spicy (ginger and winter melon) Chenin (amphora) to a lean tannic bone-dry Chenin (whole bunch/amphora) to a leesy, honeyed Chenin (barrel-ferment).

Over a flight of finished Anima Chenin Blanc from 2009 to 2015, Johnathan demonstrated the core minerality of Avondale soils – how expressive and textured the wine gets as it ages, how the primary fruit develops secondary flavours: the bright yellow fruit, the spicy, beeswax nuances. “We’re after ageability. The concept of using your own yeast - is an important part of slow winemaking. The flavour esthers come to the fore during a slow ferment. Commercial yeast ferments wine very quickly. When we consume younger white wines, they only show primary fruit.”

We tasted on a root day on the biodynamic calendar – not a preferred flower or fruit day (leaf days are also out). Johnathan says, “The big debate is whether a tasting is about the wine or the taster, or both?” Chef Eric Bulpitt of new Faber restaurant at Avondale created my best winelands meal of the year to date – starring Avondale duck bacon with government bean velouté, braised mutton and creamed Prieska grits with Avondale carrots, and Avondale pecans mousse strudel with farm carrot curd. Wow!

My learning curve in the classic art of amphora ended at Grande Provence wine estate in Franschhoek. New winemaker/GM Matthew van Heerden led a tasting of new releases including a delightful maiden Zinfandel 2013 and their flagship Amphora 2015 (at R650 only ex-cellar). Made by predecessor Karl Lambour (now GM at Tokara), Grande Provence Amphora is made from Chenin Blanc sourced from 34-year-old vines in Franschhoek – and fermented on the skins in Italian amphora. A dash of Viognier and Muscat de Frontignan lifts the concentrated natural fruit of Chenin. Made by Manetti Gusmano and Figli of Florence, seventh generation Tuscan artisans, these imported 400-litre amphorae come at a price - costing some R60 000 per vessel.

“The wine is a complete departure from what one expects from a white wine – balanced tannin, deeply coloured and aromatic,” adds van Heerden. Pressed Viognier skins were added to enhance aroma and texture. The grapes were left to ferment naturally on the skins in 400-litre clay amphorae for seven months. Wines crafted in this way require less sulphur for stability as tannins from seeds and skins are a natural preservative, while the clay vessels allow the wine to ‘breathe’ during ageing.

Prior to bottling, the wine was transferred to an old 500-litre oak barrel. Van Heerden concludes, “The wine is zingy, fresh and aromatic. Upfront flavours of mandarin and citrus on the nose carry through beautifully onto the palate, complemented by hints of perfume from the Viognier skins. When I taste this truly unique wine, it becomes apparent that with careful natural winemaking we can craft wines that are a pure expression of their site, with complex layers of texture and intense fruit aromas.”

Yeas ago I first spotted a row of wine amphora at the Museum of Antiquities in Cairo, in the King Tutankhamen exhibit. The contents had long evaporated but not the mystique – along with the name of the head of the vineyard depicted in hieroglyphics.

Aarco Larman, ex-winemaker at Glen Carlou – watch out for his new eponymous range of Cluster Wines, especially Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon – first introduced me to unwooded Chardonnay fermented in large concrete “eggs”. French vat manufacturer Marc Nomblot’s family has been making these concrete wine vats from Loire sand, gravel, non-chlorinated spring water and cement since 1922 – and has seen a surge in orders since 2001. Winemakers from Australia to California claim the (amphora) shape enables a slow liquid flow, better fermentation kinetics, uniform temperature (especially with natural yeast) and better lees suspension – preserving natural varietal character, freshness and purity of fruit and flavour aromas, body and weight – without adding wood flavours or reductive notes (Sally Easton, MW).

Winemaker Duncan Savage of Savage Wines, comments, “We started the amphora project at Cape Point Vineyards in 2006 to use South African made pots as opposed to French oak. The pots are quite oxidative, making them fantastic for fermentation and for a style less focused on upfront aromatics. The pots are also great conductors, which makes managing ferment temperatures and the like really easy. For years we fermented Semillon in the pots, but I started working with Grenache and Cinsaut on the skins in amphorae. The results are amazing and gave birth to ‘Follow the Line’” (his acclaimed Cinsaut, Grenache and Shiraz blend. (Good Taste, January 2016)

Anthony Hamilton Russell is another pioneer of amphorae in South Africa. He has used these vessels since 2005 as a blending component for his Chardonnay and white Sandstone blend under the flagship Ashbourne label. (Sandstone is being discontinued due to huge production costs.) At the time AHR pointed to the benefits of amphorae, saying: “It’s the same air exchange as a barrel but without the flavour of oak. It’s not so much a taste thing as a structural thing”. The amphorae “enable the wine to develop without vanillins and tannins – and might also help red wines in “avoiding oak spice and getting purity of fruit” (The Drinks Business, May 2012)

Eben Sadie, the innovative winemaker at Sadie Family Wines, twice winner of Platter’s Winery of the Year, is another advocate. He has constructed a special amphorae cellar at his Malmesbury winery to extend the dedicated facility for the making of his flagship Palladius (Chenin-led) blend, fermented and lees-aged in clay and concrete amphorae. He says, “It adds more depth and structure to the wine, but doesn’t let wines go flabby; they stay linear, dense and tight. It’s finer stitching”.

Gilga, a boutique wine label from cellarmaster Stefan Gerber in Stellenbosch, was inspired by an ancient legend of amphora. It depicts Gilga, a beautiful courtesan of the great Persian King Amurabi, drinking from a terracotta amphora. Shunned by the King, she decides to end her life and drinks from an amphora marked “poison”. The story has a happy ending. The “poison” turns out to be Shiraz fruit wine from the vineyards of Shiraz which fermented in the clay amphora and turned into wine. Every time Gilga visits Amurabi, he orders the uplifting “poison” in his palace chamber.

The wheel has turned full circle in the new age of the amphora. Watch this space. And if you spot any of these curious eggs and amphorae in the cellar, make sure to ask the winemaker what he’s up to - and if you can taste the contents. You’ll be surprised.