Emile Joubert explains what makes them so renowned along with tasting notes on some notable wines.

The world might be awash with tens of thousands of different wines from every country imaginable, but in essence there are only two types of vinous offerings: those made from single grape varieties and those that combine two or more cultivars, blended by the winemaker to present a whole that is deemed greater than the sum of its parts.

For the wine lover, the composing of a blended wine has two attractions. Firstly, the amalgamation can offer a palate-pleasing wine that provides not only all-encompassing drinking pleasure, but also immense complexity. Those imbibers, for example, who find a single-cultivar wine such as Cabernet Sauvignon a bit tannic and forceful in the mouth will experience a plusher and more agreeable wine once the Cabernet Sauvignon has been given a juicier veneer with the addition of a splash of Cabernet Franc and Merlot. The same goes for a white wine, where the pungent grassiness of Sauvignon Blanc is toned down and fleshed out by dropping some fuller-bodied Sémillon into the mix during the winemaking process.

As to the second important factor of blended wines, think branding power, status and pure presence. Here some of the greatest international and South African wines are known simply by one name, a name that represents the combination of grapes used in creating this merging of cultivars. Like the great wines of Bordeaux.

The appeal and value of legendary wines like Château Margaux, Lafite and Mouton Rothschild rest on their Bordeaux origin, provenance and status – and quality, of course – far more than it does on the grape varieties used to create them. The same goes for California’s revered Opus One and the Australian hero that is Penfolds Grange – New World wines that have gained mythical status almost rivalling that of the Bordeaux luminaries. In each of these instances, the wine’s name and the brand are all-encompassing, commanding attention for the reputation for quality it has built over decades and representing the individuality and style of the bottle’s cherished contents.

In the South African context this feature is particularly relevant because it has largely been blended red wines that have staked their place at the forefront of the local industry’s reputation. I would challenge even the most knowledgeable vinophile to deny that KWV’s Roodeberg, a blended red, was the most famous Cape wine offering in the 1970s and early 1980s. No one really cared whether this wine was made by bringing together Shiraz, Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinotage or whatever else might have gone into those mysterious bottles. The fact of the name Roodeberg said enough.

And despite tremendous improvements in viticulture and winemaking that have seen exceptional single-variety Cabernet Sauvignon, Shiraz, Cabernet Franc and Merlot wines made in South Africa today, our most famous red wines are still blends with big names: Meerlust Rubicon, Kanonkop Paul Sauer, Rust en Vrede Estate, Eben Sadie’s Columella. It must also be said, though, that some of the country’s most popular wines, on which many wine drinkers cut and stained their teeth, are blended. Think Nederburg Baronne, Chateau Libertas and that perennial favourite of students, Tassenberg.

Rust en Vrede is situated on the lower slopes of the Helderberg Mountain and is some 15km from False Bay. Shielded by the mountains from the powerful South Easter as well as South Westerly, Rust en Vrede has a warmer microcosm that is ideal for reds, particularly Shiraz and Cabernet Sauvignon.

Pioneer of all the Cape’s esteemed blended red wines, Stellenbosch’s Alto Rouge must surely take pride of place in terms of pioneer status. The Alto Estate, on the Annandale Road outside Stellenbosch, has been making its blended Rouge since 1922 and to my mind deserves far greater recognition for its role in establishing a culture of multi-cultivar wines to a degree of consistent excellence than is currently the case.

It was here on the slopes of the Helderberg that then-owner Manie Malan became impatient with the time it took Alto’s Cabernet Sauvignon to soften while maturing in oak barrels. The four-year ageing period to rid the wine of its tannic thrust was not conducive to marketing sensibilities and the consumers’ need for an approachable, fruit-driven red wine.

Manie understood the plush nature of Shiraz and Cinsaut, the other two main varieties grown on Alto, and used these in blending with his Cabernet Sauvignon to create a wine that was accessible and fully drinkable two years after harvest.

By 1924 Alto was exporting this blend exclusively to Burgoyne’s wine shop in London, as the trader deemed this Cape stuff to be a spitting image of the red wines from the magical wine region of Burgundy in France – a fact that will no doubt have today’s wine buffs choking on their Pinot Noir.

The international popularity of this Alto Rouge saw it being released onto the South African market in 1933 – 90 years ago. The fact that this wine still has pride of place in today’s environment is truly a momentous achievement and recognition of the commitment to its legacy by those who followed in Manie’s footsteps.

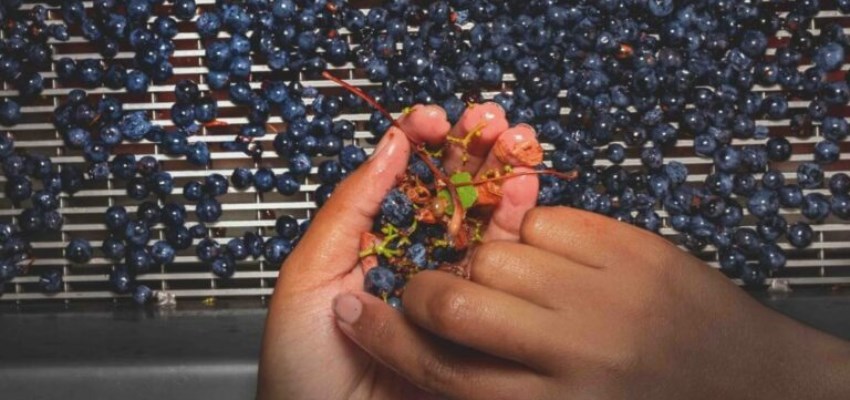

Over the years and under the stewardship of various legendary cellar masters, the Alto Rouge blend has been adapted from that first vintage as the winemakers sought to improve the wine’s quality in reflecting the terroir of Alto and to use new developments in viticultural practices and the availability of different clones. The primary components in Alto Rouge today are Cabernet Sauvignon, Shiraz and Cabernet Franc, with Petit Verdot and Merlot also incorporated to add complexity and depth.

History and nostalgia aside, under the wine-making prowess of current cellar master Bertho van der Westhuizen the Alto Rouge continues to be a superb red wine, punching way above its weight in terms of the price-to-value ratio and staking its claim as a true South African great of immortal status.

At Tokara, traditional methods are used alongside leading-edge technology to produce wines that express a unique sense of place. The farm lies between two beautiful valleys on the foothills of the Simonsberg and only grapes from the best blocks are used for their Bordeaux-style blends.

The Bordeaux connection

It was during the 1970s that the South African wine industry took the few earnest steps that would help it progress to becoming a more serious wine country that was dedicated to underscoring the principles of recognising terroir and defining its diversity of wine regions. This decade saw regulations passed to define areas of grape production officially through the Wine of Origin scheme, as well as allowing for the making of estate wines grown, made and bottled within the borders of individual wine farms. Before then the majority of the industry was used to carting grapes and wine from farm cellars to the major wine corporations, where the fruits of the farmers’ labour were thrown together into big brands, some of which were nondescript and soulless.

This more serious wine environment led to farm owners being able to now realise dreams and implement methods to express themselves and the individual nature of their properties’ soils and climate in an attempt to bring a new degree of class and distinction to Cape wine. And like most other wine farmers around the world, they saw Bordeaux as the ultimate reference point.

Looking back to that time, it must be said that the South African wine industry has missed a beat by not bestowing enough honour on the late Billy Hofmeyr. It was he who made the country’s first Bordeaux-style red blend in 1979 on his Paarl wine estate Welgemeend, and it was he who believed that the Cape had terroirs capable of achieving greatness in classic red wines. It was also he who had influence on preeminent winemakers such as Jan Boland Coetzee, Walter Finlayson, Etienne le Riche and Kevin Arnold, making him as much a source of inspiration as a brother in South Africa’s vision of creating fine wine.

Billy was no trained winemaker, but a quantity surveyor.

To read the full article, click HERE.